Even people who accept the Hard Problem as real still often make a distinction between cognition on one hand and qualitative subjective consciousness on the other. Cognition, presumably, is amenable to analysis in terms of information processing, and may in principle be performed perfectly well by a computer. It encompasses Chalmers's "easy problems". Subjective consciousness, or qualia, is the answer to "what is it like to see red?", i.e. the Hard Problem. Qualia is the spooky mysterious stuff that no purely informational or functional description of the brain will ever account for.

I would like either to clarify or eliminate the distinction. What exactly do we mean by "cognition"? When we speak of cognition in a computer, is it really the same thing that we are talking about when we speak of cognition in a human being? When we speak of "cognition" and "qualia", what are the distinguishing characteristics of each, such that we can be sure that some event in our minds is definitely an example of one and definitely not the other? The line between what we experience qualitatively and what we think analytically or symbolically is very hard, if not impossible, to draw. Even with the most purely qualitative impression, there is a troublesome second-orderliness - there is no gap at all between seeing red and knowing that you are seeing red.

Recall that my zombie twin is an exact physical (and presumably cognitive) duplicate of me, but without any subjective phenomenal experience. It walks and talks like me, and for the same neurological reasons, but is blank inside. There is nothing it is like for it to see red. Horgan and Tienson (2002) suggest an interesting thought experiment that turns the zombie thought experiment on its head.

Imagine that I have a twin whose phenomenal experiencings (i.e. qualia) are identical to mine throughout both of our whole lives, but who may be physically different, and in different circumstances (perhaps an alien life form, plugged into the Matrix, or having some kind of hallucination, or a proverbial brain in a vat). The question that screams out at me, given this scenario, but that Horgan and Tienson do not seem to ask (at least not in so many words) is this: to what extent could my phenomenal twin's cognitive life differ from my own? If the what-it-is-like to be it is, at each instant, identical to the what-it-is-like to be me, is it possible that it could have any thoughts, beliefs, or desires that were different from mine?

Now we may quibble over defining such things in terms of the external reality to which they "refer" (whatever that means), and decide on this basis that my phenomenal twin's thoughts are different than the corresponding thoughts in my mind, but this is sidestepping the really interesting question. Keeping the discussion confined to what is going on in our minds (that is, my mind and that of my phenomenal twin), is there any room at all for its cognition to be any different from mine? If every sensation it has, every pixel of its conscious visual field, every sensation, every emotion, everything of which we might ask "what is it like to experience that?", is it possible that while I was thinking about how to get rid of the wasps in my attic, it was thinking about debugging a thorny piece of software? (Charles Siewert (2011) makes similar points in his discussion of what he calls totally semantically clueless phenomenal duplicates.)

Think of a cognitive task, as qualia-free as you can. Calculate, roughly, the velocity, in miles (or kilometers) per hour, of the earth as it travels through space around the sun. Okay. Now remember doing that. Besides the answer you calculated, how do you know you performed the calculation? You remember performing it. How do you know you remember performing it? Specifically, what was it like to perform it? There is an answer to that question, isn't there? You do not automatically clatter through your daily cognitive chores, with conclusions and decisions, facts and plans spewing forth from some black box while your experiential mind sees red and feels pain, and never the twain shall meet. There is, of course, a ton of processing that happens subliminally, just as there is a ton of perception that happens subliminally. Nevertheless, just as there is a definite what-it-is-like to taste salt, you are aware, consciously, experientially, of your cognition. But what exactly is the qualitative nature of having an idea?

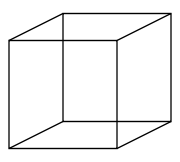

David Chalmers has asked whether you can experience a square without experiencing the individual lines which make it up. This question nicely underscores the blurriness of the distinction between qualia in the seeing red sense, and cognition in the symbolic processing sense. When you see a square, there is an immediate and unique sense of squareness in your mind which goes beyond your knowing about squares and your knowledge that the shape before you is an example of one. What is it like to see a circle? How about the famous Necker cube? When it flips for you, to what extent is that a qualitative event, and to what extent is it cognitive?

It's not an illusion, really. There is no sense when the cube flips for you that anything in your field of vision changed. Even a child can see with complete confidence that the lines on the paper did not change at all, but something in the mind did. This is in contrast to illusions in which, say, a straight line appears bent, and you are actually deceived. So the "raw experience" of black lines on white paper did not change, and there is not even a subjective sense that they did, but something changed.

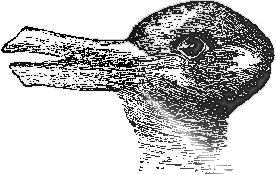

The thing that changed has something about it that seems easy-problemish, in that it is about a cognitive inference, a second-order interpretation of the actual lines. Nevertheless, it is visceral, and immediately manifest, as much as the redness of red. Your "cognitive" interpretation of the cube (i.e. whether it sticks out down to the left or up to the right) has its own qualitative essence that outruns the simple pattern of black lines that you actually see. You might say that there is cognitive penetration of our experiences, but you could just as accurately say there is experiential penetration of our cognitive inferences. The classic duck/rabbit image is similar. You can't merely see; you always see as. What is it like to see the word "cat"? Wouldn't your what-it-is-likeness be different if you couldn't read English, or any language that used the Roman alphabet? Your cognitive parsing of your visual field is inseparable from the phenomenology of vision.

What is it like to have a train of thought at all? How do you know you think? What is it like to prove a theorem? What is it like to compose a poem? In particular, how do you know you have done so? Do you see it written in your head? If so, in what font? Do you hear it spoken? If so, in whose voice? You may be able to answer the font/voice questions, but only upon reflection. When pressed, you come up with an answer, but up to that point you simply perceived the poem in some terms whose qualitative aspects do not fit into the ordinary seeing/hearing categories.

Among people (pro and con) who use the word "qualia", there is a tendency to characterize qualia as exclusively sensory, and to think that any "qualia of thought" are qualitative only by inheritance. That is, we actually "hear" our thoughts in a particular auditory voice, or see things in our minds' eye. I, for one, don't think in anyone's voice. Moreover, any qualia of thought is not just tagging along in the form of certain charged emotional states that accompany certain kinds of thoughts. All conscious thought is qualitative. The qualia is right there, baked into the thoughts themselves, as such. "Purely" "cognitive" "content" is itself qualitative, not just the font it is written in, or the voice it assumes when it is spoken, or the hope or the fear that we attach to it.

Anything we experience directly, whether it is the kind of thing we usually associate with sensation and emotion or with dry reasoning and remembering, is qualitative: a song, a building, a memory, or a friend. By definition, all I ever experience is qualia. Even when I recall the driest, most seemingly qualia-free fact, there is still a palpable what-it-is-like to do so. To the extent that our cognition is manifest before us in the mind in the form of something grasped all at once, whether in the form of something which is obviously perceptual or something more abstract, it is qualitative. How do you know you are thinking if you in no way express your thought physically (writing or speaking it)? A thought in your mind is simply, ineffably, manifestly before you, as a unitary whole, the object of experience as much as a red tomato is.

That we are aware of our thoughts at all in the way we are is no less spooky and mysterious than our seeing red. If you were a philosopher who was blind since birth, the "what is it like to see red?" argument for the existence of qualia would not have the same impact that it does on a sighted person. If you were also deaf, neither would "what is it like to hear middle C on a piano?". If you were an amnesiac in a sensory deprivation tank, would you have any reason to worry about these mysterious qualia that philosophers think about so much? You would, simply by virtue of noticing that you had a train of thought at all.

"What is it like to see red" or "what is it like to hear middle C on a piano" vividly illustrate the point of the Hard Problem to someone approaching these topics for the first time, but it is a mistake to stop at the redness of red. The redness of red is the gateway drug. Just because the existence of qualia is most starkly highlighted by giving examples that are non-structured and purely sensory, it is wrong to think that the mystery they point to is confined to the non-structured and purely sensory.

Even my fellow qualophiles are often to quick to accept the qualia/cognition distinction, however. The paradigmatic examples of qualia are good for convincing people that we don't yet have a solid basis for understanding everything that goes on in our heads. It is tempting, however, to think that we are at least on our way to having a basis for understanding what is going on in our heads when we think. My point is we don't have a good basis for understanding that either.

I understand that this is a naked appeal to my readers' intuitions. We have already crossed that rubicon back in the first chapter with the introduction of the Hard Problem, qualia, and the redness of red. If you reject all of that, okay, I guess, but if not, if you accept the Hard Problem as real, upon reflection you must accept this as well. If you think there is anything deeply mysterious about the redness of red, you should be just as troubled by the thoughtiness of thought.

Just as qualia are not just the alphabet in which we write our thoughts, neither are they merely the raw material that is fed into our cognitive machinery by our senses. The qualia are still there in the experience as a whole after it has been parsed, interpreted and filtered. Qualia run all the way down to the bottom of my mental processing, but all the way up to the top as well. We are not, to steal an image from David Chalmers, a cognitive machine bolted onto a qualitative base. Nor, as Daniel Dennett says (derisively), is qualitative consciousness a "magic spray" applied to the surface of otherwise "purely" cognitive thought. Each moment of consciousness is its own unique quale; new qualia are constantly being generated in our minds.

There are qualitative experiences that accompany, or even constitute, cognitively complex situations, but which are nevertheless no more reducible to "mere" information processing than seeing red is. Once, looking down from the rim of the Grand Canyon, I saw a hawk far below me but still quite high above the canyon floor, soaring in large, lazy circles. I was hit with a visceral sense of sheer volume - there is no other way to describe it. I felt the size of that canyon in three dimensions, or at least I had the distinct sense of feeling it, which for our purposes is the same thing. This was definitely something I felt, above and beyond my cognitively perceiving and comprehending intellectually the scene before me. At the same time, the feeling is one that is not a byproduct or reshuffling of sense data. After all, as a single human being I only occupy a certain small amount of space, and can have no direct sensual experience of a volume of space on the order of that of the Grand Canyon. Had I not experienced this feeling, I still would have seen the canyon and the hawk, and described both to friends back home. The feeling is ineffable - there is no way to convey it other than to get you to imagine the same scene and hope that the image in your mind engenders the same sensation in you that the actual scene did in me.

Nevertheless, the feeling that the scene engendered in me only happened because of my parsing the scene cognitively, interpreting the visual sensations that my retinas received, and understanding what I was looking at as I gazed out over the safety railing. The overall qualitative tone of a given situation depends crucially on our cognitive, symbolic interpretation of what is going on in that situation. Further, the individual elements of a scene before us have qualia of their own apart from the quale of the whole scene. For example, there may be a red apple on a table in a room before me, and the image of the apple in my mind may have the "red" quale, even though it is part of and contributes to the overall quale I am experiencing of the entire room at that particular moment. The impression of the whole room, however indistinct this impression may be at the edges, is what it is, all-at-once, a quale. There is a whole-room-including-the-apple quale, and that incorporates a redness-of-red quale. The purported primitive, unstructured, sensory qualia somehow are still there, immediately, in the parsed, cognitively saturated qualia.

There are some entire types of qualia, moreover, that are inherently inseparable from their "cognitive" interpretation, experiential phenomena that are especially resistant to attempts to divide them into pure seeing and seeing-as. In particular, as V. S. Ramachandran and Diane Rogers-Ramachandran pointed out (2009), we have stereo vision. When we look at objects near us with both eyes, we see depth. This is especially vivid when the phenomenon shows up where we don't expect it, as with View Masters, or lenticular photos (those images with the plastic ridges on them that are sometimes sold as bookmarks, or that used to come free inside Cracker Jack boxes), or 3D movies. This effect is, to my satisfaction, unquestionably a quale. It is visceral. It is basic. You could not explain it to someone who did not experience it.

At the same time, it is obviously an example of seeing-as, part of your cognitive parsing of a scene before you. One might possibly imagine some creature seeing red without any seeing-as, unable to interpret the redness conceptually in any way, but it is impossible to imagine seeing depth in the 3D way we do without understanding depth, without thereby automatically deriving information from that. To experience depth is to understand depth, and to infer something factual about what you are looking at, to model the scene in some conceptual, cognitively rich way. Stereoscopic vision is our Promontory Point, where the Hard and easy problems collide. It is an entire distinct sense modality, but one that is inextricably bound up in our informational processing of the world.

What we know informs what we experience. I take it as pretty much self-evident that it is almost impossible to have a "pure" experience, stripped of any concepts we apply to that experience. Everything we experience is saturated with what we know, or think we know, what we expect, what we assume, etc. In terms of my actual direct experience of a visual field, I don't have a raw bitmap, I have a scene, with stuff in it, and all that stuff has certain characteristics. I see this blob as a hydrant, that one as a cloud, this splotch as the sun, that one as an object that I could touch, and that will probably persist through time. However experiences happen in minds, they are probably the result of lots of feedback loops at lots of different levels, all laden with associations and learned inferences, all stuff we might call cognition. There is no such thing as pure seeing, separated out from any seeing-as.

Through an act of willful intelligence, I could decide to concentrate only on those things in a scene before me that begin with the letters M, N, and G. Alternatively, I could choose to pay special attention to those things made of metal. In the same way, through willful, intelligent effort, I can try to distill some "pure experience" from the scene, and come up with something like a raw bitmap, perhaps for the purpose of painting a picture on a canvas of the scene.

Even in the case of our old friend, the redness of the apple, our immediate experience is that of a red apple, not some free-floating redness of red. It is by an effort of willful abstraction that we distill the image of the apple into this purported redness quale, distinct from any cognitive parsing of the scene. But even if this effort could possibly ever be 100% successful, this is further processing, more cognition, not less. The actual immediate qualitative conscious experience is that of an apple, sitting on a plate on a countertop, all mashed up with whatever thoughts we have about the apple, or apples in general, trailing off at the edges in a penumbra of memories and associations. The whole all-at-once thing is a quale. For this reason, it is a bit backwards to think that I am starting with my cognition-soaked experience and working to get back to the "raw" experience, because that presumes there was originally such a thing to get back to.

This represents something of an expansion beyond what is commonly meant by "qualia" in the literature. If we are to carve Nature at its joints, we should not stop at this intellectualized, abstracted redness of red. The whole experience is a quale, and any attempts on our part after the fact to decompose an experience into components is additive, not subtractive. You haven't reduced anything that way. If my readers get nothing out of this book other than a somewhat more expansive notion of "qualia", I will take that as a win.

Our thoughts and experiences are not the mindless clattering of "cognitive" machinery all the way down, but rather qualia all the way up. In some way, our ineffable qualia are interwoven with our judgments, conclusions, assumptions, and thoughts. It is a step in exactly the wrong direction to conclude from this that knowledge and concepts can take full responsibility for experience, and that knowledge and concepts are among Chalmers's "easy" problems, solvable within the framework of reductive materialism. This step entails discarding qualia altogether, and concluding that experience is cognition all the way down. Nevertheless, this is the step, more or less, that Daniel Dennett takes.

Daniel Dennett (1991) makes a great deal of the difficulty of distinguishing clearly between experiencing something as such-and-such, and judging it to be such-and-such. In response to an imaginary qualophile, Dennett says, "You seem to think there's a difference between thinking (judging, deciding, being of the heartfelt opinion that) something seems pink to you and something really seeming pink to you [emphasis his]. But there is no difference. There is no such phenomenon as really seeming - over and above the phenomenon of judging in one way or another that something is the case." (p. 364). In Consciousness Explained, Dennett gives many examples that serve to undermine our faith that we really do experience what we think we experience, and there are many others that are not in his book. That said, I can't help but smile at the fact that even he used the qualitatively loaded term "heartfelt" in the way he did in the quote above - seems like begging the question a bit given the argument he is making.

Dennett says to imagine that you enter a room with pop art wallpaper; specifically, a repeating pattern of portraits of Marilyn Monroe. Now, we only have even reasonably high-resolution vision in our fovea, the portion of our field of vision directly in front. The fovea is surprisingly narrow. We compensate with saccades - unnoticeably quick eye movements. Even with the help of these saccades, however, Dennett says, we could not possibly actually see all the details of all the Marilyns in the room in the time it takes us to form the certain impression of being in a room with hundreds of perfectly crisp, distinct portraits of Marilyn. I'll let Dennett himself take it from here:

Now, is it possible that the brain takes one of its high-resolution foveal views of Marilyn and reproduces it, as if by photocopying, across an internal mapping of the expanse of wall? That is the only way the high-resolution details you used to identify Marilyn could "get into the background" at all, since parafoveal vision is not sharp enough to provide it by itself. I suppose it is possible in principle, but the brain almost certainly does not go to the trouble of doing that filling in! Having identified a single Marilyn, and having received no information to the effect that the other blobs are not Marilyns, it jumps to the conclusion that the rest are Marilyns, and labels the whole region "more Marilyns" without any further rendering of Marilyn at all.

Of course it does not seem that way to you. It seems to you as if you are actually seeing hundreds of identical Marilyns. And in one sense you are: there are, indeed, hundreds of identical Marilyns out there on the wall, and you're seeing them. What is not the case, however, is that there are hundreds of identical Marilyns represented in your brain. Your brain just somehow represents that there are hundreds of identical Marilyns, and no matter how vivid your impression is that you see all that detail, the detail is in the world, not in your head. And no figment [Dennett's term for the metaphorical "paint" used to depict scenes in his Cartesian Theater - figmentary pigment] gets used up in rendering the seeming, for the seeming isn't rendered at all, not even as a bit-map.

The point here is that while we may think we see the Marilyns on the wall, and we may think that we have a qualitative experience to that effect (just like our qualitative experience of seeing red), this is almost certainly not the case. Instead, what is happening is that we have inferred, or judged that there are Marilyns all over the wall, and we have a very definite, certain feeling that we actually see these Marilyns. Sometimes we think we directly experience things that are right in front of our faces, but really we just conclude that we have experienced them. Our inability to tell the difference is intended to make qualophiles like myself uneasy.

Dennett also discusses the blind spot in our visual field. There are simple experiments that demonstrate that a surprisingly large chunk of what we normally think of as our field of vision is not actually part of our field of vision at all. We simply can not see with the part of our retina that is missing because of where the optic nerve leaves the eyeball. The natural, naive question is, why don't I notice the blind spot? The equally natural, and equally naive explanation is that the brain compensates by "filling in" the blind spot, guessing or remembering what should be seen in that region of the visual field, and painting (applying more figment) that pattern or color on the stage set in the Cartesian Theater.

Dennett is quite emphatic that nothing of the sort happens. There is no Cartesian Theater, so no filling in is necessary. There is no such thing as seeing directly, there is only concluding, so once you conclude (or guess, or remember) what should be in the blind spot, you are done. There is no inner visual field, so there is no need for inner paint (figment), or inner bit maps. We do not notice the blindness because "since the brain has no precedent of getting information from that gap of the retina, it has not developed any epistemically hungry agencies demanding to be fed from that region".

I think I am being fair to Dennett to characterize his basic claim as follows: we think that our direct experience is mysterious, but often it can be shown pretty straightforwardly that when you think you are directly experiencing something, really you are just holding onto one end of an inferential string, the other end of which you presume to be tied to this mysterious experiencing. Given this common and easily demonstrated confusion, it is most likely that all purported "direct experience" is like this, that all we have is a handful of strings. We never directly experience anything; we just judge ourselves to have done so. We never see, we only think we see. Even the redness of red.

Materialists like Daniel Dennett often use optical illusions as examples. You thought you saw one thing, but it actually turned out to be another! Or even, your judgment about your perception itself turned out to be wrong, and if your judgment about your "direct" perception is fallible, well, that's the whole game, right? We certainly should not make sweeping metaphysical pronouncements based on something that could just be wrong. Perhaps not, but the purported wrongness is a minor detail in these cases. Even the "wrong" perception proves the larger point. We can be mistaken in our judgments about our perceptions, but we can not be mistaken about having perceptions at all. The circle of direct experience may be smaller than we usually think, or it may have less distinct boundaries, but we can not plausibly shrink it to a point, or out of existence altogether.

It may impossible to draw a clear distinction between experience and judgment, but this is because judgment is itself a sort of structured experience. There is no naive experience: our judgments are part and parcel of our perceptions. Nevertheless, it is interesting that Dennett never clearly and simply defines "judgment". Computers do not know, judge, believe, or think anything, any more than the display over the elevator doors knows that the elevator is on the 15th floor. All they do is push electrons around. Even calling some electrons 0 and others 1 is projection on our part, a sort of anthropomorphism. It seems as though I see all the Marilyns; Dennett says no, I merely judge that I see them. He is right to force us to ask ourselves how much we really know about the difference. He is wrong to think that the answer makes either one of them less mysterious, or more amenable to a reductive, materialist explanation.

It is kind of like the difference between having a map showing a place you need to drive to, and having a GPS feeding you a list of directions to that place. You can follow the directions, turning where they say to turn, without ever forming any overall conception of where you are or where you are going. The GPS can even tell you how to get back on track if you make a wrong turn. You can simply follow the directions, and never "put it all together" into any bird's eye, directional sense of where you are.

Could it not be the case that even when we do have a sense of where we are, say, in the middle of our home town, that sense is an illusion, and all we really have is a really good set of directions for how to get any place we might need to go? When it comes right down to it, is there any real difference between "directly" perceiving something in all its detail on one hand, and having on-demand answers to any questions you might pose about that thing on the other? Could it be the case that we think that we have an immediate, all-at-once conception or perception of something, but all we really have is an algorithmic process that is capable of answering questions about that something really quickly, a just-in-time reality generator?

If I think I have a conception of something, say, a soldering iron, could it turn out that really there is nothing but an algorithm, a cognitive module in my head with specific answers to any question I could have about the soldering iron? At any point, in any situation, the algorithmic module would produce the correct response to any question about the soldering iron in that situation. How to use it, what it feels like, its dangers, its potential misuse, its utility for scratching my name with its tip into the enamel paint on my refrigerator. Such a module would serve as a just-in-time reality generator with regard to any experience I might have involving the soldering iron. It would consist of a bundle of expectations of sensory inputs and appropriate motor outputs regarding the soldering iron.

To use computer terminology, as long as the soldering iron algorithmic module presented the correct API to the rest of the mind, isn't it possible that the mind is "fooled" into thinking that it has a qualitative idea of the soldering iron, when all it really has is a long list of instructions mapping input to output? Is there really any difference between the two ways of characterizing our cognitions regarding soldering irons? No, It is not possible, and yes, there is a difference. When I see the soldering iron, I really do see it. The sense I have of that, even with its tendrils of inference and association extending into the shadows, is itself the explanandum here, just as the redness of red was in chapter 1. What is the sense that I see all the Marilyns if not itself a quale?

The difficulty with cleanly distinguishing between "directly" perceiving something and merely judging it to be a certain way, (while having specialized modules for answering questions about it) is not limited to visual perception or perception at all, in the usual narrow sense. Nor is it limited to perception of the outside world. The same kinds of ambiguity exist with regard to our understanding of our own minds. I believe the sun will rise tomorrow. Do I really hold this single belief, or is it just a huge bundle of expectations and algorithms, each pertaining to specific situations or types of situations that I might find myself in?

Any of the unitary things we naturally posit in our minds (models, images, memories, beliefs) could have some component at least of such a bundle of algorithms, or agents. For any such thing, what is its API to the rest of the system, really? How much can we really say about the underlying implementation that instantiates that API? Maybe I just infer somehow that I have a belief that the sun will rise tomorrow, but that "belief" is not nearly the short little statement written down somewhere that it seems to be. The articulation of the belief could, as Dennett suggests of all of our articulations, be the result of some kind of consensus hammered out by lots of demons or agents. Nevertheless, the sense that I have such a belief is real, and unitary, even if some kind of computational mechanism that contributes in some way to that sense is not. Could I really have that sense of believing the sun will rise tomorrow without actually holding that belief?

Frankly, I don't know right now what a belief is, or what a judgment is, when it comes down to it. It may, however, not be enough to characterize them only in terms of the functional role they play in our cognitive architecture, which is to say, in terms of the API they present to the rest of the system, while remaining implementation-agnostic. At the very least, anyone who wants to dismiss qualia as "merely" complexes of judgments or beliefs must make the positive case that judgments and beliefs can and should be characterized entirely in non-qualitative terms themselves.

Many philosophers agree that in minds, qualitative consciousness and cognition are closely related, if not two ways of seeing the same thing, but make the mistake of concluding that qualia must therefore be merely information processing, which we think we understand pretty well. "Information" is a terribly impoverished word to describe the stuff we play with in our minds, even though much of what is in our minds may be seen as information, or as carrying information. Shoe-horning mind-stuff into the terms of information theory and information processing is a homomorphism, a lossy projection. There are no easy problems in the easy vs. Hard Problem sense. The way the mind processes information has a lot more in common with the way the mind sees red than it does with the way a computer processes information.

Once again, the computer beguiles us. Of course, we created it in our own image, so it is no surprise that it ends up being an idealized version of our own intuitions of how our minds work. We understand computers down to the molecular level; there are no mysteries at all in computation. And clearly, in some sense at least, computers know things, and they represent things. I can get some software that will allow me to map my entire house on the computer, to facilitate some home improvement projects I have in mind. And lo! my computer represents my couch, and seems to understand a lot about its physical characteristics, and it does so completely mechanically. We can scrutinize what it is doing to achieve that understanding all the way down to the logic gate level and beyond. We are thus confident that we know exactly what is going on when we speak of knowledge, representation, information processing, and the like. There is nothing mysterious here, at least in the mechanics of what is going on. It is a simple step from there to imagine that the brain, for all its neural complexity, is (just) a computer in all the relevant ways, and we only need to figure out its implementation details.

Just because we can design devices that simulate a lot of the functions of cognition, this does not mean that these simulations do it the way we do it, any more than a computer connected to a video camera correctly identifying a red apple sees red. In terms of our understanding how minds do what they do, I'm afraid the easy problems are hard too.

My zombie twin identifies the apple as red, and exclaims about its redness the same way I do, but by hypothesis, it does not really see the redness the way I do. It "sees" but does not see. You may not agree with this, but I hope at this point you at least understand what I mean by that. By the same token, my zombie twin "plans" summer vacations, "worries" about its taxes, and "believes" the sun will come up tomorrow, but to say that just because its internal causal dynamics are identical to my own internal causal dynamics, it really plans, worries, and believes is to make a big, and I think, wrong statement about the nature of planning, worrying, and believing. At best, you are using those terms loosely, in the same way we say a magnet knows about a nearby piece of iron. Just because we understand computers, and computers seem to know, think, remember, infer, etc. we should not therefore think that now we understand those things.

We do not study cave paintings as clinically accurate diagrams to learn about the human and animal physiology depicted therein. We study them to learn how their ancient creators saw themselves and their world, to get inside their heads. The real insights to be gained into the mind from computers come from considering that this, this particular machine, is how we chose to idealize our own minds. We do not study cave paintings as accurate depictions, but to get inside the heads of the people who made them. The real insights about minds to be gained from computers come from considering that this is how we chose to idealize our own minds.

I can write "frozen peas" on a grocery list, and thereby put (mechanical) ink on (mechanical) paper. Later, when I pull out the list at the store, and it reminds me to put frozen peas in the cart, this physical artifact interacts with photons in a mechanical way. The photons then impinge upon my sensory system, and thus, in turn, my mind. So the paper and ink system represents frozen peas; it knew about them. Of course, most computers we use today are a bit more complex than the paper grocery list, but the essence is the same - there is the same level of knowledge, representation, information processing, etc. going on in each. We can say that in a sense, the list really does know about the frozen peas, but not in a way that necessarily gives us any insight at all into how we know about peas.

There is no "pure" cognition in the mind, at least none that we are directly aware of. Over a century ago, philosophers did not separate cognition and qualia the way they do now. It was only in the early part of the 20th century, in the ascendance of behaviorism and the advent of Information Theory and Theory of Computation that we Anglophone philosophers started thinking that we are beginning to get a handle on "cognition" even if this qualia stuff still presented some problems. When some thinkers felt forced to acknowledge qualia, they grudgingly pushed cognition over a bit to allow qualia some space next to it in their conception of the mind, so the two could coexist; now they wonder how the two interact.

The peaceful coexistence of cognition and qualia is an uneasy truce. Qualia can not be safely quarantined in the "sensation module", feeding informational inputs into some classically cognitive machine. We must radically recast our notions of cognition to allow for the possibility that cognition is qualia is cognition. Qualia are not just some magic spray that coats our otherwise functional machinery, or some kind of mood that washes over our minds. Qualia are what our minds are made of, the girders and pistons as well as the paint. This is the bullet I am biting in this chapter, that of expanding the notion of qualia beyond the paradigmatic unstructured sensory experiences, to include lots of other phenomena as well, many that are not sensory, and quite structured indeed.