"…however complex the object may be the thought of it is one

undivided state of consciousness."

-William James

"…however complex the object may be the

thought of it is one undivided state of consciousness."

-William James

The All-At-Onceness of Conscious Experience

Way back in the first chapter, we looked at the Hard Problem, which

for people of a certain temperament is a bit radical in its

implications. This is the idea that you can never account for

the redness of red with a story about causal bonking alone, no matter how

much you dress up the bonkings with fancy words like "refer",

"algorithm", or "information". Trying to fix this problem by

looking at the bonkings from a "high level", or collecting

them into black boxes, as functionalism does, does not work either.

Given the reality of phenomenal consciousness, this is troubling

beyond the problem of explaining consciousness, because it tells

us that any framework for understanding reality (like physics, as

currently construed) that consists, at bottom, of a story about

causal bonkings is at best incomplete. The redness of red gives us

a counter-example to the causal bonking story.

I hope by now that you accept all of this, and that you agree that

the Hard Problem is a real problem. If so, you are in

reasonably good company - lots of philosophers are

troubled by the redness of red.

The redness of red is just the tip of the iceberg, however.

Some physicalists brush the Hard Problem aside as a mere

intuition. Maybe it is, but for reasons I have already covered, it's

an awfully compelling one. In this chapter, I ask you to accept

what seems, as first, as an even kookier one, and one that is a

bit more abstract, but one that I

think is just as compelling. In fact, it is really just a logical

extension of the original redness-of-red Hard Problem. If you

accept one, you should accept the other. Same bullet, maybe

another set of tooth marks.

As we encounter things in the world around us, when do we judge

something to be just a heap or aggregate of smaller things,

like a pile of sand, and when do we judge it to be a true, unified,

single thing? It depends, almost always, on how you look at it.

When we look at the world in strict

reductionist terms, nothing above the sub-atomic level really

counts as a holistic thing.

Are there any things above the micro

level that really are inherent, single things in a way that does

not depend on how you look at them?

Do we have any reason to believe that there

are, in contrast to the reductionist view, inherently unitary mid-level

things in the universe? Put another way, if some philosophical

pedant says, "That's not a table, it's just a bunch of atomic

matter arranged in a tablewise fashion", are there any

things in the world (excepting the atomic components themselves)

of which this is simply not true? Is there anything you could

show the pedant and say, "No, that is just absolutely a table."?

We do, in fact, have evidence of

such things, and the evidence, as with the redness of red, is our

own phenomenal consciousness.

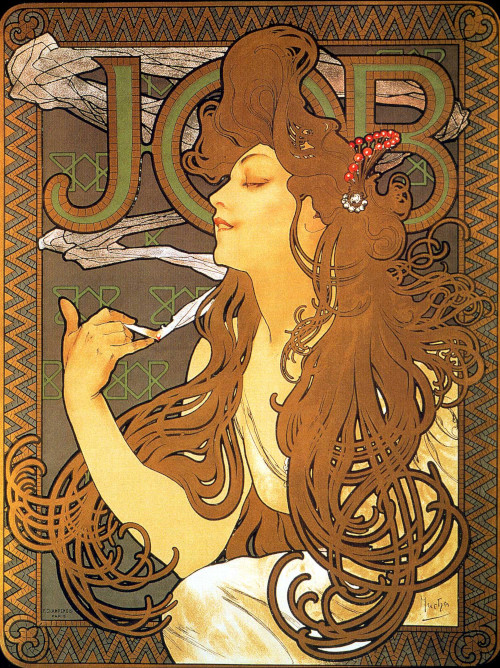

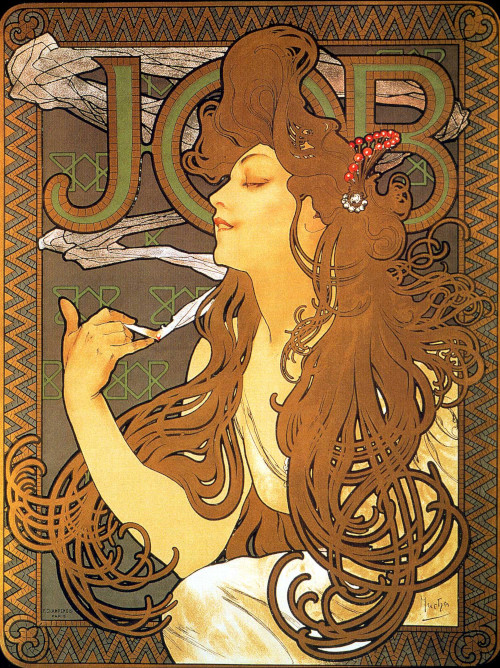

I have an art nouveau poster in which a woman is smoking,

and there is a stylized curl of smoke rising from her cigarette.

When I look at that languid asymmetrical curve,

I see the continuous curve in its entirety, all at once. I do not just

have some kind of cognitive access to the fact of the curve. The

parameters of the curve are not just available to me upon making

certain kinds of

inquiries. I do not just have a pointer or reference to a lot of

data beyond my view that yields results pertaining to the

curve when evaluated. The details of my perception are not just at my

fingertips, but bam! right there, live, all at once. I see the

whole curve now. This is every bit as undeniable as the redness of red.

However you might nibble at the edges of my perceptual field, there

is a wholeness to that curl of smoke that is manifest before me, in

a qualitative way.

I have an art nouveau poster in which a woman is smoking,

and there is a stylized curl of smoke rising from her cigarette.

When I look at that languid asymmetrical curve,

I see the continuous curve in its entirety, all at once. I do not just

have some kind of cognitive access to the fact of the curve. The

parameters of the curve are not just available to me upon making

certain kinds of

inquiries. I do not just have a pointer or reference to a lot of

data beyond my view that yields results pertaining to the

curve when evaluated. The details of my perception are not just at my

fingertips, but bam! right there, live, all at once. I see the

whole curve now. This is every bit as undeniable as the redness of red.

However you might nibble at the edges of my perceptual field, there

is a wholeness to that curl of smoke that is manifest before me, in

a qualitative way.

In contrast,

of an intelligent computer with its video monitor aimed at

the curve (LDA, STA, JMP…),

all we can say is that at some level

it may be thought of (by us) as seeing the curve. That is, given an

abstract understanding of its algorithm and data structures,

one may interpret the functioning of the machine as

"seeing" the curve. This, however, is anthropomorphizing on our part,

albeit on the basis of the computer's deliberately programmed design.

As with seeing red, any claims about what a computer could or could

not perceive apply equally to my zombie twin. We have no principled way

of saying that the zombie sees the curl of smoke, in spite

of its ability to answer questions about it, report on it,

or makes claims that it sees it. We are faced with the

same failure of entailment, the same explanatory gap as we were

with the zombie seeing red.

There is, in contrast, nothing

"may be thought of" about my seeing the curve. It

is not a matter of interpretation. It is an absolute fact of Nature

that I really do see that curve all at once, before me.

Seen at the low level, as an ant-like CPU crawling over

data gravel, there is no inherent sense in which "it all

comes together" for a computer, whereas there is an inherent

sense in which it all comes together for me.

This is not just another "I see red, the computer will never see

red" argument (although it is related).

The "seeing red" arguments focus on

qualitatively rich but nevertheless cognitively simple aspects of

experience. I am talking instead about our ability to have cognitively

complicated scenes before us in our mind's eye,

to see the complex as one thing, all at once in its entirety:

e pluribus unum. Assuming we take the Hard Problem seriously,

as we think of the sorts of mental phenomena that compel us

to do so, we often cite the good old redness of red, tickles,

itches, pains, saltiness, etc. as paradigmatic qualia. But once

we go that far, this wholeness-quale is just as troubling.

It is just as much an essence as the taste of ice cream is

in the Hard Problem sense.

I would like to distinguish this unity of

conscious percepts from the so-called binding

problem, however. The binding problem refers to the fact that, for

example, the visual processing parts of the brain and the auditory

processing parts are quite different, and in fact take different

amounts of time to do their jobs. In spite of these facts, we can have a

single experience that incorporates elements from several

senses at the same time, and they are synchronized. The binding

problem is fascinating in its own right, but what I am talking

about here is, I think, at least as fundamental. I am concerned not so

much with the way in which different sense modalities (vision,

hearing, smell, etc.) can be bound together in a single percept,

but how anything at all, even within a single sense

modality, can have the kind of unity it does. This qualitative gestalt

is every bit as strange and inexplicable as the redness of red.

Even my fellow qualophiles do not pay enough attention to this.

It could be argued that my percept of a tree is not an indivisible

whole: you can break it into parts (leaves, branches, trunk).

But that only means that

I have a tree percept, then, often by effort of willful analysis,

I have a subsequent follow-on percept of tree parts, albeit possibly with

tendrils of reference reaching back to the original

unitary tree percept.

Just because a cathedral is made of stones,

it does not follow that my conception

of a cathedral is made of my conception of stones.

Even if my

conception of the cathedral incorporates the knowledge of the

stones, there is still a single experienced percept of the

cathedral that subsumes this fact.

My percepts are immediately, manifestly unitary whole things.

Regardless of the cognitive or physiological

mechanism which supports them, they serve as

a counter-example to the doctrine of ontological reductionism.

I know I perceive my percepts, and that those percepts really are

whole objects just as certainly as I know I see red.

Things, in my mind, are qualia, as are all abstractions -

manifestly before me, all at once.

Out in the world, there may be only a bunch of atomic

matter arranged in a tablewise fashion, but in my mind,

if only in my mind, there is a table.

Consciousness gives us not only examples that there are such

things as qualitative essences in the universe, but also that there

are such things as things. This claim

may strike some people as a case of comparing apples and oranges.

"Just because you perceive something as

an inherent whole doesn't mean it actually is an inherent whole",

one might be tempted to argue. "You are just interpreting it that way."

But it is the percept itself, the interpretation

(if you must call it that), not the

thing out there in the world that is being perceived, that I am

talking about. "Your percept only seems like a unified

whole" is analogous to the claim that "electromagnetic

radiation at around 430 THz only seems red".

It is that seems part that we have to explain.

My claim here is that the seeming of unity must itself be a unity.

If these percepts are things in the deep, inherent

sense that I claim,

how many are there? What are their boundaries? Is that stylized

curl of smoke really itself a thing, or part of the larger percept

of the poster as a whole, or even some even bigger percept, one

that is even connected by filaments of association to others, or

memories, who knows what? I don't know (yet). There is more work

to be done to answer these questions. The point here is that

we only need a tiny bit of unity to break the reductionist's

claim. Maybe I don't really see as much or as clearly beyond

the center of my field of vision as I think I do, maybe I am

susceptible to all kinds of illusions that demonstrate how hard

it is to specify the edges of my percepts, but as long as I see

any of that curl of smoke, we need to say how that could possibly be.

We must take first person experience seriously, both in

the seeing red case and in the case of the unity of our percepts.

Both (and perhaps more besides) must be explainable in any final

theory of nature we concoct. Such a theory must include principles

of individuation that allow for the mid-level things that are my

percepts.

Gregg Rosenberg

discusses this quite a bit (although from

a somewhat different perspective). To use his term, we need a

theory of natural individuals.

So when I claim that these unities, however they are demarcated, are

some kind of true, inherent, fundamental unities, am I talking about,

well, physics? Yes I am. As with the redness of red, I think we need to

go all the way down with this. Otherwise we are left with some kind

of functional unity made of blind causal bonking, and that would not

give us the qualitative sense of that curl of smoke as a curl, any more

than it would the color of the poster's background.

There are inherent, absolute things above the level of

the quark, but below the level of the whole universe itself.

These mid-level things may only exist in our minds, but that is enough

to say that they do exist.

Like my seeing red, these things in my mind can not be illusory.

If it seems that there are mid-level

unitary things among my percepts, then those seemings themselves

must be mid-level unitary things.

For my unitary percepts to manifest

themselves to me as they do, they can not just consist of smaller parts

integrated only through causal dynamics, bits bonking blindly into other

bits, with some sort of functional description emerging from the bonking,

any more than the redness of red can.

Whatever the crumbs are out of which

the universe makes everything else, these things count among them, rather

than things built out of the crumbs. They are just bigger crumbs than

the kind we are used to.

I want to emphasize that when I say that my conscious perceptions are

"mid-level" things,

I am talking about the scale (between quark and universe), and

definitely not implying that these things occupy some middle level of

a tree of organization. In that sense, the whole point is that these

are low-level things. They are big and complex, yet they must

count as primitive objects. They can't be exhaustively characterized

in terms of any lower level of description or analysis.

There is certainly a huge number of possible

conscious percepts - quite possibly infinite. All this being true,

we live in a universe in which there is a huge

(possibly infinite) number of fundamental

components, these components have qualitative essences, and most of them

are big and rich, not tiny and simple. Any formulation of

reductionism that could accommodate these facts would hardly be

worthy of the name.

In the last chapter, I characterized reductionism as consisting of these

premises:

-

everything in the universe is made of simple building blocks

-

anything we choose to study may, in principle if not in

practice, be defined and

described completely in terms of the simpler building blocks of which

it is made

-

there is a finite (and small at that) number of types of

these basic building blocks

-

each instance of a particular

building block is interchangeable with any other instance of that

same building block (one electron is absolutely identical to

another electron)

-

these building blocks are entirely

characterized by their functional dispositions (i.e. they have no

qualitative essence, just behavior, such as that described

by the lowest-level equations of physics)

What I am saying in this chapter is that our percepts and thoughts,

whatever else we may say about them, definitely violate #3, #4, and

#5. We are left with a baroque universe, with a huge mess of

primitive components, a lot of which are big.

It is worth noting, however, that this view is nevertheless reductionist

in a sense. Everything in the universe may well be reducible in

principle to its component parts - it is just that there is no

small number of such fundamental components in the universe,

and a lot of those fundamental components are pretty

substantial things in their own right. The important respect in

which it still counts as a form of reductionism is that under

this view, you do not get anything out that isn't there in

the lowest levels. Specifically, this view does not posit any magic

"emerging" from a system on the basis of its "complexity" or

functional organization. Complexity and functional organization,

defined in causal terms, smeared out across time, and dependent on

lots of hypotheticals, doesn't confer the kind of inherent, just-is,

really-there kind of qualitative essence we need to account for the redness

of red, nor the manifest all-at-onceness of our percepts.

Neuron Replacement Therapy

There is a popular thought experiment that goes like this. Suppose

that neurologists characterized each neuron's inputs and outputs

exactly, and were able to engineer a functional equivalent. That

is, an artificial device whose inner workings may or may not be

similar to those of a natural neuron, but whose behavior, seen in

terms of its responses to inputs, was identical to that of a

neuron. Now suppose that the neurons that comprise your brain were

replaced with these artificial neurons, one by one. Once your

entire brain was cut over to the artificial neurons, you should

have a brain system whose functioning at the neuronal level is

identical to that of the brain you were born with, but whose

workings are entirely artificial, and as such, able to be

characterized with an algorithm of some sort.

This thought experiment (called Neuron Replacement Therapy, or NRT for

short) is intended to put anti-physicalists and

anti-functionalists like me in an uncomfortable position.

We either have to say

that the resulting artificial brain is not conscious (and if not, at

what point in the gradual neuron replacement does consciousness

disappear, and when it does, does it wink out all at once or fade

out gradually), or we must admit that the artificial brain maintains its

consciousness, and therefore full-blown consciousness is realizable

by a machine.

Thoughts Are Evidence Of Mid-Level Holism

I agree that there is nothing magic about organic or biological

systems. There is no reason that consciousness must be manifested

in a biological system. Indeed, as a panpsychist, I think

that consciousness in some form is likely manifested all the time

in all kinds of matter. The problem with the thought experiment is

that it begs the question - it presumes exactly the functionalist

reductionism that is, in my opinion,

at the heart of the matter. It assumes that

what makes a brain a mind does so purely by virtue of

the complex interaction of lots of blind little autonomous parts, each

not knowing or caring about the others, as long as each has the right

interface presented to it.

No one knows the details of the relationship between neurons

(as neuroscientists characterize them) and

consciousness, but thoughts come whole, nose to tail.

A given percept, thought, or moment of consciousness

is what it is in its entirety, all at once, or not at all.

It has no parts, so you can not swap some of its parts out in favor of

"functionally equivalent" parts.

Functional Organization Can't Solve Panpsychism's Combination Problem

Even if a thought or percept is an example of some kind of fundamental

holism occurring in nature, couldn't it still be generated in some

way by the orderly, lawful interactions of smaller parts? Possibly,

in some sense, but it could not turn out to simply be the

orderly, lawful interactions of smaller parts, not in the way the

hurricane just is the the orderly, lawlike interactions of

trillions of water and air molecules.

The interactions of parts may functionally emulate

a percept, and they may support it somehow,

or give rise to it causally, but they alone can not be it.

Assuming that there will, ultimately, turn out to be necessary

relations between the physical world as we understand it and

consciousness, the physical correlates of consciousness would have

to display or allow for the kind of holism that our thoughts manifest.

This has implications beyond the physicalists' arguments about NRT.

Contrary to what Phil Goff and Luke Roelfs say,

panpsychism's combination problem can not be solved by functional

organization alone. Even if the quarks are seeing red, feeling pain,

or craving transcendence like crazy, any aggregation of them can not

be a basis for larger-scale consciousness if that aggregation is

achieved through billiard ball bonking.

Panpsychism's combination problem can not be

solved by functional organization alone. Even if the quarks are seeing red

and feeling pain like crazy, any aggregation of them can not be a basis

for larger-scale consciousness if it is achieved through billiard ball bonking.

The "integration" or "high levels" you can

get out of causal poking, over time, characterized in terms of

unrealized hypotheticals, can't give you the intrinsic all-at-onceness

we experience, no matter how hard the quarks are rooting for us.

I want to be clear about the bullet I am biting.

I think epiphenomenalism

is wrong - qualitative consciousness has

observable, causal powers in the physical world.

Moreover, it has an inherent, indivisible unity, which is at least

as weird as its qualitative aspect (that old redness of red).

We either have to be orthodox physicalists,

or we must embrace some freaky holism at work in the

world: really-there holism, not just may-be-seen-as holism, holism

that has causal implications that somehow have escaped the notice

of the people in the white lab coats.

Physicalists hate this sort of thing - I have an intuition of

qualitative properties, or holism, and on the basis of that

intuition I make huge claims about the fundamental building

blocks of the physical universe. Oh, and by the way, these claims

entail causal happenings that ought to be empirically

falsifiable. I appreciate the distaste for this, but I

can not see how I could explain away these "intuitions" without

making such claims. To twist the slogan of the New York Times,

I am here to draw all the conclusions fit to draw, without fear

or favor.

I am placing my bets on there

being something in the physical world that manifests this, something

causal that exists as a whole at a much larger scale than an electron.

I am insisting on something that violates the apparent causal closure of

physics, or at least bends it quite a bit.

Where in the physical world might we find this kind of

inherent wholeness, as opposed the to just may-be-seen-as wholeness

that functional analysis of systems of parts gives us?

Quantum Mechanics

It has been said that

the reason that so many people relate consciousness to

quantum mechanics is a sort of conservation of mysteries:

consciousness is mysterious, quantum mechanics is mysterious, so

maybe they are the same mystery. While the connection between them

is admittedly circumstantial, they are mysterious in similar enough

ways that we may speculate that at the very least quantum mechanics

is a promising place to look for consciousness in the natural world.

(See Seager (1995) for a similar line of speculation).

First, we seek a place for consciousness at the very lowest levels

of nature. As I've already argued, you can't build it out of

the causal dynamics of the lower levels bonking into each other.

Taking the Hard Problem seriously, I claim, forces us to be

panpsychists, and that means putting consciousness (or something

that scales up to consciousness as we know it) way down

on the ladder of stuff in the world. Quantum mechanics is the

lowest rung on the ladder, as low as our understanding of the

natural world goes. It is the layer of inquiry of which we know

only the behavior of the things we study,

but we can not, in principle, know the intrinsic nature

of whatever is doing the behaving. No one knows what an electron

really is, beyond our ability to characterize its extrinsic behavior as

described by the relevant quantum laws. It is at this level, following

Russell, that we ought to find consciousness.

Second, and more to the present point, at least as striking as the

qualitative nature of consciousness (what is it like to

see red?) is the all-at-onceness of our thoughts and perceptions,

their intrinsic unity.

Quantum mechanics gives us some counter-examples

to the orthodox reductive physicalist way of seeing everything big and

complex as (mere) aggregates of tiny simple things.

The very strange world of

quantum mechanics is populated by bunches of things that come together to form

one larger thing that can really no longer be thought of as

a heap of separate components. In a quantum entangled system

consisting of two particles, for example, we have

multiple parts coming together to

form a thing that is inherently, absolutely, one single unitary thing,

whose behavior is described (and plausibly could only be

described) by a single Schrödinger wave function.

Over the decades, there has been a fair amount of hand-wringing over

the limits of this quantum holism. Is there just one big wave

function for the entire universe? What really separates a system

under study from its environment at the quantum level? These

questions have not been answered to this day, but there is no

doubt that some kind of real, ineliminable macroscopic holism exists

out there in the physical world.

As with our percepts, a quantum entangled system is one

thing, not an aggregate that may be seen as a thing when looked at

or analyzed a certain way. The ontological reductionism inherent in

a classical or Newtonian view of the natural world means that

consciousness can not find a home in a world that is

exhaustively described by such a view. Because quantum mechanics

sidesteps this reductionism by providing a real basis for holism in

the universe, by process of elimination, we ought to

strongly suspect that consciousness and quantum phenomena are

somehow related.

This idea is a version of what is called

strong emergence, where truly new stuff comes into existence

when you arrange low-level things in certain ways,

as opposed to the weak emergence of the flock from

the birds. See (Silberstein 2001) for a discussion along these lines.

(With regard to consciousness, then, I am a strong

emergentist, although I'm not sure I love that term. It seems a bit

woolly and open-ended, and the term "emergence" might not quite

capture what is ultimately going on. Moreover, it is still, in spite of

the qualifying adjective, a little too adjacent to its weak

sibling for my taste, given that I think that they are fundamentally

different phenomena.)

Third, there is the problem of the alleged

causal closure of the physical world, and the way quantum mechanics,

and the holism it implies, allows us to wiggle out of it.

The argument is often made that the

laws of physics are airtight, that (assuming they are true) they

account completely for everything that happens in the world,

leaving no room for consciousness to have any measurable effect on

anything. Unless, that is, you define consciousness strictly in terms of

physical dynamics in the first place, which is to say that you

subscribe to physicalism (and thus, in my opinion, define away the

interesting questions and properties of consciousness).

Sean Carroll (Goff & Moran, 2022),

for one, bangs this drum a lot. He gets a bit

exasperated with us panpsychists, who claim, on the basis of

our first-person intuition, that the most successful, precisely

quantified theory in the history of humankind, must be wrong.

He stresses that our theories of fundamental physics (the "core theory")

may have some soft spots, or uncertainties around the edges, but

those limits are way, way, way outside the realm of

anything that happens in a human brain. The claim that the core theory

is wrong at normal energy levels, in what we consider a normal

gravitational field, while not logically ruled out, must clear

an almost laughably high bar.

Point taken. Can we have a robustly causal panpsychism that

does not so much contradict the well-established results of

quantum mechanics as supplement them?

It certainly seems that the laws of quantum mechanics are true, and

dead-on accurate. The loophole in the causal closure argument

may be that, while perfectly accurate, the laws of quantum mechanics

only yield probabilities from an empirical point of view.

They specify a distribution curve, not precise predictions.

They predict collective behavior with 100% accuracy, but are

agnostic about individual behavior.

If you run a quantum experiment

10,000 times, you are assured that your outcomes will fit this

distribution curve exactly, and for any one trial, the probability

of one outcome over another is determined by the curve, but quantum

mechanics is famously unable to tell the specific outcome of a

particular single trial. It is an inherently indeterministic

theory. Moreover, it is generally accepted that this indeterminacy

is not a flaw in the theory or evidence of its incompleteness, but

a fundamental feature of physical reality itself.

No matter how well you know an electron's initial conditions, once

it is in flight, you can not

predict its position before you measure it. This is not because

of any practical limitation on our ability to characterize the

initial conditions of the electron, or any inaccuracy in the

theory, but because the electron can not properly be said to

have any definite position before you measure it. The

position of the electron before you measure it is literally

unknowable. It has only a

likelihood of being in one place, and a different likelihood of being

in another place. So the best theory we have about how the physical

world behaves and most interpretations of that theory are, when it

comes right down to it, indeterministic about the precise behavior of the

physical world at a low level.

The only possible exception to this is the possibility that there

are some kind of as-yet undiscovered "hidden variables" at work,

and once discovered, they will allow us to predict the electron's

position once more with Newtonian accuracy. Albert "God does not

play dice" Einstein spent a great deal of his later life looking in

vain for a hidden variable theory. Very few people seriously

entertain the possibility of hidden variable theories today. Such

theories are regarded as a philosophically (rather than scientifically)

motivated attempt to restore determinism to the physical world.

Even in the classical (i.e. non-quantum) world, it is

becoming more apparent all the time that

chaos

and non-linear dynamics are the norm. Tiny differences at a low level get

amplified to huge differences at a high level (as in the oft-cited

butterfly effect).

There is no reason,

therefore, that we would need particularly large-scale quantum

phenomena to have a substantial effect on the macroscopic world

around us.

"Random" Is A Big Tent

People mean different things at different times by the word "random",

But mathematicians have a pretty specific thing in mind when they

use the term. You may have a hat containing ten cards,

each with a different numeral written on it, from 0-9. You may draw

cards from the hat, writing down the numeral drawn each time, then

putting the card back for the next draw. It is quite unlikely, but

perfectly possible, for you to draw 0123456789, or 111333555777.

You could say, colloquially, that these resulted from fair "random"

drawings of cards from the hat, and that therefore the resulting

sequences are random. A mathematician, speaking technically, would

tell you that no, those weren't random at all. The digits do not

display a random distribution.

In contrast, the first digits of π are 314159265358979. Colloquially,

you might say that those digits aren't random at all, since they are

carved in stone, written into the fabric of the universe. But the

mathematician would say, no, those are random, even though they are

calculable, and derived deterministically.

When the equations of quantum mechanics say something is random,

they are not making any ontological claims about how the numbers

came to be; they are merely like our mathematician, observing that

they display a certain conformance to a distribution curve.

There are many different actual outcomes of a given set of trials

of an experiment that would still perfectly fit a

given distribution curve, and thus not violate any laws that were

given strictly in terms of conformance to such a distribution curve. The

statistical distribution of letters I type on a keyboard might be the same

whether I am typing a sonnet, a recipe, or meaningless gibberish.

A complex coherent pattern may have the same statistical

distribution as random noise - indeed, any maximally dense information,

(i.e. maximally compressed information), is statistically

equivalent to random noise by definition.

The door is open, at any rate, for

patterns to result from the behavior of quantum systems whose

coherence is not predicted by quantum theory, but which

nevertheless does not violate the predictions that quantum theory

does make. We can squeeze the causal efficacy demanded by

non-epiphenomenal panpsychism through a loophole in the stochastic

nature of quantum predictions without actually contradicting the

established theory.

So - quantum mechanics allows for the existence of high-level entities

that are causally efficacious, and whose behavior, while

constrained by other entities, has an element that can only be

called "random" by our best third-person physical theories.

Maybe consciousness occurs in bursts, in the collapse of quantum

superpositions, as

Hameroff and Penrose claim.

Maybe some kind of large-scale quantum superposition

is sustained in the warm, wet environment of our brains by using the tubulin

cytoskeleton of our neurons. Maybe not. Something like that, something

crazy sounding, however, will turn out to be the case.

I speculate that at some point in the future it will be

discovered that the brain's activity depends crucially upon quantum

phenomena, which are amplified to the level of neurons firing.

Of course, the operative word here is speculate. It is worth

noting that it is only under certain special types of circumstances

that quantum systems can evolve in a state of entanglement or

superposition without decohering or collapsing back to a classical

state (leaving aside the philosophical thicket of the measurement

problem). Under ordinary circumstances, we do not see quantum

systems of any great scale (I avoid using the word "complexity"

because it implies precisely the wrong thing, namely that a quantum

system is made of parts, and that there may be fewer or more of

those parts). So like Hameroff, I suspect that we will

eventually find structures in the brain that would support some

reasonably large-scale quantum superposition which implies

isolation from the surrounding environment.

But Back To NRT

Physical systems in states of quantum entanglement display

holism that I claim is a non-negotiable necessity for

instantiating consciousness.

Further, I have speculated that as quantum mechanics contains the only currently

known gap in the causal closure of the physical, the

indeterminacies of quantum mechanics are, in fact, the fence around

these natural individuals that modern science has built, with a

sign that says, "Something funny is going on in here, and we can

never know what".

For the moment, however, let us set aside my suspicions

about quantum mechanics.

Perhaps my speculations about quantum mechanics are completely wrong.

Perhaps consciousness is some kind of hitherto undiscovered field

or force that is modulated or generated by neurons. Maybe

Gregg Rosenberg

is right, and consciousness is built into the mesh of causation

itself. Moreover, no matter how this question is answered,

the quantum superposition or force or field that is consciousness

could be something that

spans lots of neurons, as Hameroff and Penrose believe,

or it could be something that happens inside

a single neuron, as suggested by

Jonathan Edwards.

Whatever kind of physical phenomenon thoughts, percepts, or moments

of consciousness turn out to be at the most fundamental level,

neurons have evolved to generate or exploit this phenomenon in some way.

But it must be they, (these fields, forces,

superpositions, collapses thereof, or whatever) that

instantiate consciousness in the senses I am interested in

for the purposes of this book: the redness of red, and the

holistic unity of our thoughts and percepts. The missing

physical link is something weird, and not the supporting

neuronal infrastructure.

If the the artificial neurons in the NRT thought experiment

can also exploit or generate these

things, then great - consciousness is preserved in the artificial

brain. If not, not, and the NRT thought experiment fails.

If the field or force or superposition or whatever physical blob

that instantiates this holistic consciousness spans

multiple neurons, it will not be something that can be carved up and

characterized in terms of quantifiable inputs and outputs between

neurons. In such a case the NRT hypothesis is untenable.

If, on the other hand, the stuff of consciousness (force, field,

whatever) happens inside individual neurons, it could be that

the artificial neurons will

not be able to emulate natural neurons with an explicitly

specified algorithm. In this case, the non-algorithmic

stuff in the neuron guides the neuron's behavior in non-algorithmic

ways. Otherwise, if the stuff in the neuron is emulatable

with an algorithm (the epiphenomenal case) the

end result of NRT will be a zombie. All of its neuronal behaviors

and motor outputs will be identical to those of a conscious mind,

but it will not, in fact, be conscious, at least in the "what is it

like to see red" sense.

Either way, whether whatever instantiates consciousness spans

neurons or is somehow curled up inside an individual neuron and

manifests itself causally only by influencing how and when the

neurons fire, there is something weird going on, something

physically weird. I am flatly claiming, in Patricia Churchland's

phrase, that there is "pixie dust in the synapses", except that it's even

worse than that. In past chapters,

I have emphasized the qualitative aspects of the pixie dust, which

implicitly leaves open the possibility of a more benign, conservative

panpsychism: there is weirdness, but the weirdness might be

confined to the crumbs of physical reality, and everything scales up

according to the usual rules of causal dynamics that describe how

reality stacks neatly. Here I am going a bit further in my claims

about the pixie stuff. It's not just dust. Maybe pixie clumps, or pixie blobs.

Moreover, as with the redness of red, for the same reasons,

epiphenomenalism is false:

the pixie blobs influence (or even constitute)

our cognition, and have macroscopic causal effects on the

world. The pixie blobs do stuff.

This entails taking realism about consciousness to a new level.

There is more to the mystery of phenomenal consciousness than

accounting for some kind of qualitative paint that coats the

otherwise coldly cognitive objects and data structures in our

minds. Qualia are not just unstructured sensory qualities, but

the objects themselves as well. To the extent that this

essential objecthood is perceptible to us, and figures into our

cognitive lives (i.e. to the extent that epiphenomenalism is

just as false with regard to this wholeness-quale as it is

with regard to the redness of red) this must go all the way down.

The way we think of physics must accommodate it.

I have an art nouveau poster in which a woman is smoking,

and there is a stylized curl of smoke rising from her cigarette.

When I look at that languid asymmetrical curve,

I see the continuous curve in its entirety, all at once. I do not just

have some kind of cognitive access to the fact of the curve. The

parameters of the curve are not just available to me upon making

certain kinds of

inquiries. I do not just have a pointer or reference to a lot of

data beyond my view that yields results pertaining to the

curve when evaluated. The details of my perception are not just at my

fingertips, but bam! right there, live, all at once. I see the

whole curve now. This is every bit as undeniable as the redness of red.

However you might nibble at the edges of my perceptual field, there

is a wholeness to that curl of smoke that is manifest before me, in

a qualitative way.

I have an art nouveau poster in which a woman is smoking,

and there is a stylized curl of smoke rising from her cigarette.

When I look at that languid asymmetrical curve,

I see the continuous curve in its entirety, all at once. I do not just

have some kind of cognitive access to the fact of the curve. The

parameters of the curve are not just available to me upon making

certain kinds of

inquiries. I do not just have a pointer or reference to a lot of

data beyond my view that yields results pertaining to the

curve when evaluated. The details of my perception are not just at my

fingertips, but bam! right there, live, all at once. I see the

whole curve now. This is every bit as undeniable as the redness of red.

However you might nibble at the edges of my perceptual field, there

is a wholeness to that curl of smoke that is manifest before me, in

a qualitative way.